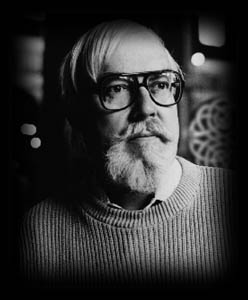

An Evening with Harry Harrison (from The Brentford Mercury):

His most famous works are undoubtedly the Stainless Steel Rat series: nine novels to date (the most recent being The Stainless Steel Rat Goes to Hell, which was published earlier this year. Like his lesser-known Bill, The Galactic Hero series, the Rat books are fun, fast and not averse to taking a gentle (sometimes not so gentle) poke at humanity.

But he's also well-regarded for his more serious works... Make Room! Make Room! (1965) deals with a seriously overpopulated turn-of-the-century New York (the book was filmed, rather inaccurately, as Soylent Green). The West of Eden trilogy is a very serious and enjoyable look at an alternative present in which the Earth was spared the calamity that destroyed the dinosaurs: it presents us with mammals and saurians evolving in parallel on separate continents, and the struggle for survival when the two races meet. Harry's most recent trilogy began with The Hammer and The Cross in 1993, which gives us an alternate medieval Earth where Christianity didn't have much of a stranglehold on Europe. It was followed in 1995 by One King's Way, and in 1996 by King and Emperor.

However, it's mostly Mister Harrison's humorous work that we discussed at our recent meeting in Dublin's Berkeley Court Hotel. The abundant background noise that you can't get from this transcript was generously provided by supporters of some football team or other, who had gathered in the bar to fortify themselves with alcohol for the arduous task of watching a football match.

To begin, I ask Harry about humour writing in general... Who does he read?

"Well, one writer who was humorous in or out of SF was Fredric Brown. Together with Mack Reynolds. They were really strong. But the problem with editors then was that many of them couldn't see how SF and humour could work together. When I first sent Bill, The Galactic Hero to Damon Knight - who at that time wrote his name with small initials, lower case, like that poet," he pauses, "e.e. cummings - he sent it back, saying 'It's a great adventure story, but take out all the jokes.'"

Harry laughs and shakes his head. "But that was the whole point of the book! It was a piss-take on Heinlein's Starship Troopers and all those gung-ho military SF books.

"Bill, The Galactic Hero came about because I'd written Deathworld - which was very grim - and the first Rat book - which was very light - and I really wanted to do something with very black humour. The later books," - a series of six sequels, the first written by Harrison alone, the rest with collaborators - "didn't really manage to capture that. In places, they worked, but not nearly so well as the first."

He continues: "With The Stainless Steel Rat it was different... The first one really was supposed to be an adventure book, and if you look at it from that point of view, that's all it is. There really aren't many jokes in there: the humour comes from the Rat's own overconfidence. Later books, like the fourth one," - The Stainless Steel Rat Wants You - "more or less have the jokes just happen to the characters... For example, there's one scene where the Rat disguises himself as the most hideous alien possible, to infiltrate the other aliens. And there he is, teeth and slime and tentacles everywhere, contacting the other races. One of the aliens takes a look at him and says 'Hello, cutie' or something like that. When I wrote that I sat up and went 'Where did that come from?' Maybe there's something about the Rat that won't let the books get too serious."

Another of Harry's works that's garnered great acclaim is Star Smashers of the Galaxy Rangers (1973). Discussing this, I mention that I read it long before I ever read any of the E. E. "Doc" Smith books of which it's a parody.

He laughs again. "A lot of people say that! When the book came out there was a pretty strong reaction to it from "Doc" Smith's fans. Some of them loved it, but some of them were cursing my name because they thought I was blackening Smith's name. But what I was trying to do was to show how silly a lot of those space operas really were. I mean, ten-mile-long space ships with five people living on them! Come on! Still, those books were good fun - I was a big fan of his work and he was a good friend of mine - but some people just took them too seriously."

Unfortunately, much of the rest of the interview is inaudible... Fans of whatever football team it was were pouring into the bar and they inconsiderately began talking loudly. Many of them were looking at us in envy, because we had chairs and they didn't. At one stage, Harry suggested that we sell the chairs.

Because of that, dear reader, this interview will now metamorphose into an article. At no extra cost.

To expand on a point mentioned in the opening paragraph, Harry is the only known author to have used his name as a pseudonym: His real name is Henry Maxwell Dempsey... The family name was changed by his father when Harry was very young. Harry later used the name Hank Dempsey to successfully sell stories to a hostile editor who wouldn't buy Harry's work because he "didn't like his style." Harry kept schtum for some time, until he one day encountered the same editor. They quickly got to discussing Harry's work, and the editor singled out Hank Dempsey's work, saying that there was someone who could really write. Harry responded with "Guess what..."

Another of Harry's humorous SF novels is The Technicolor Time Machine, in which a film crew travel back to tenth-century Scotland to make a movie about how the Vikings discovered America. In doing so, they inadvertently cause the event they're making a movie about. The book features some neat time-travel twists, and a wonderful ending... Harry says that it's this very ending that prevented the book from being filmed; I won't spoil it for you.

As mentioned earlier, the sequels to Bill are somewhat less acerbic than the original, though they do have their merits... They are all set between the last chapter and the envoi of the first book. The Planet of the Robot Slaves (1989, by Harrison alone) is probably the most successful. While not up to its predecessor's standard, it's a jolly good romp with some wonderful set pieces. Also worthwhile are The Planet of Zombie Vampires (1991, with Jack C. Haldeman II) and The Final Incoherent Adventure (1992, with David Harris).

Other humorous works include the non-SF Montezuma's Revenge (1972) and its sequel Queen Victoria's Revenge (1974), the non-fiction Great Balls of Fire (1977), The Men from P.I.G and R.O.B.O.T (chap. 1974), and lots of short stories (in particular my personal favourite, "Not me! Not Amos Cabot!").

Apart from the above, the following are essential reading: Captive Universe (1969), In Our Hands, The Stars (1970), Rebel in Time (1983), The Turing Option (1992, with Marvin Minsky), A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! (1972), Skyfall (1976), the To the Stars trilogy (from 1980), Planet Story (1979, illustrated by Jim Burns), the mostly-non-fiction Farewell, Fantastic Venus! (1968, edited with Brian Aldiss), and pretty much anything he's ever written or edited. You should also take a look at Harry Harrison (1990) by Leon Stover, an in-depth analysis of the great man and his work.

My thanks to Harry for a thoroughly enjoyable evening. Negative thanks to the football supporters who rendered much of the interview unusable. I take great pleasure in knowing that their team was slaughtered.

[Many thanks to Harry Harrison and The Brentford Mercury for the above interview.]

Bibliography:

Collections:

Non-fiction:

Non-SF novels:

As editor:

As editor with Brian Aldiss: